The Google app’s feed was introduced globally across Android and iOS devices between July and October this year. If you’re not familiar with it, it’s Google’s take on the news feed: a series of stories that you’re (supposedly) interested in.

With the feed joining voice search and other Google search formats (Images, News, etc.) as yet another way to find content, now seems like a good time to understand exactly what’s going on with it. The better that SEOs can understand how and why content appears there, the better we can optimise for it.

An immediate hurdle with Google’s feed is that, like social feeds, it’s highly personalised. As an example, I’m going to be working from the feed that I saw at 9.55am on Wednesday 6th December, but at the time of publishing my feed will look completely different and your feed (if you have one) will look completely different to both those feeds. In order to write anything close to a useful blog post, I’m forced to assume that looking at my personalised feed will throw up some underlying principles that can be applied more generally.

Google’s take on a personalised feed

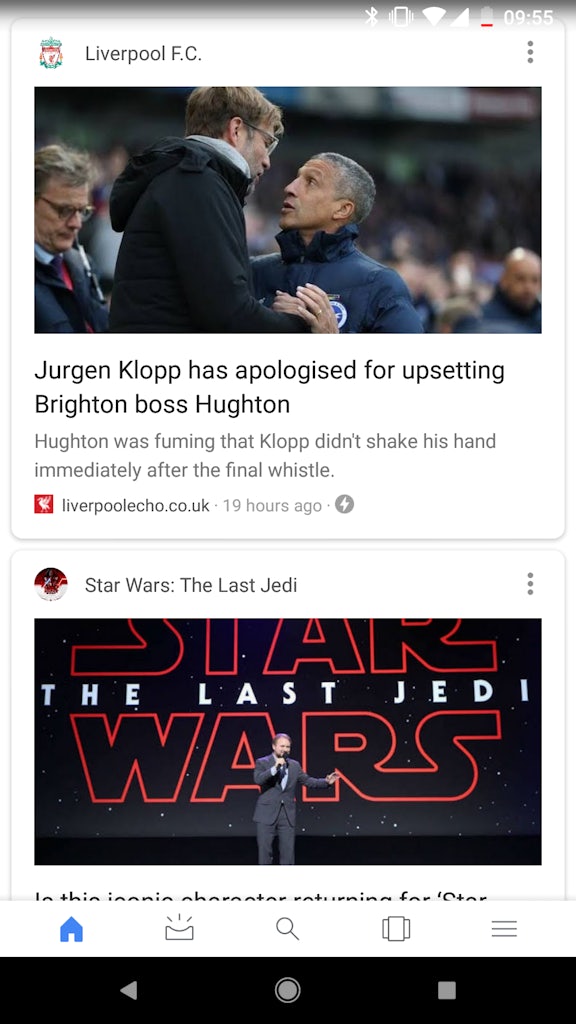

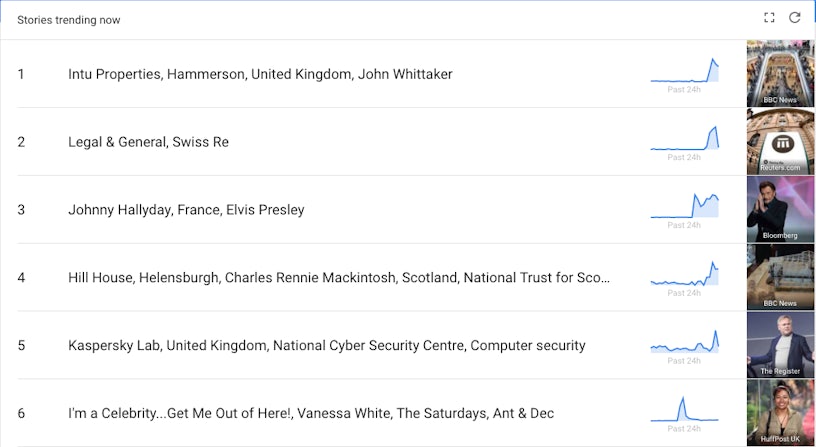

To kick things off, here’s a screenshot of the top results I saw at 9.55am on Wednesday 6th December:

Those two stories highlight two of the primary ways that the Google feed works out what content to show you: topics specified by the user and the topics that its AI thinks you’re interested in based on the data it has on you. I’ve told my Google app that I want Liverpool FC updates, but it’s worked out on its own that I also want Star Wars updates (which happens to be more accurate than some of the other stories that pop up).

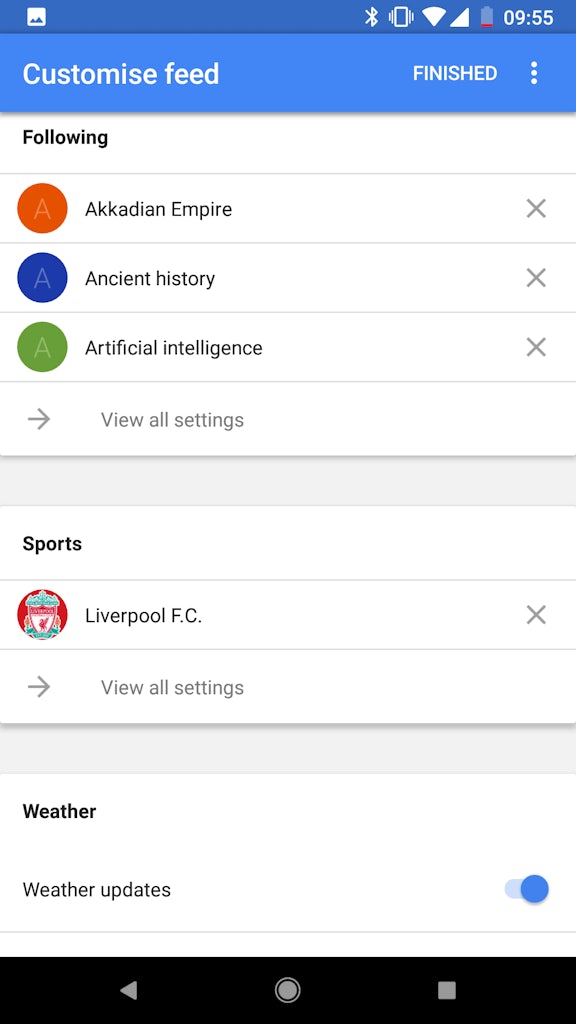

I’ve actually given my feed a relatively extensive list of topics through the ‘customise feed’ options – you can get an idea of the granularity with the screenshot below. However, plenty of interesting topics appear that I haven’t chosen specifically.

As you can see, I’ve picked a sports team to get updates on, I’ve selected a variety of other topics that I’m interested in, and I have various other updates, like the weather, set to appear as well. But how does Google go from understanding the topics I’m interested in via my settings and its own AI to choosing which content to serve? In other words, what are the Google feed’s organic ranking factors? That’s what SEOs need to understand, but it’s also the hardest question to answer.

Reverse engineering the feed’s content

At least as far as I can see, Google hasn’t given us any more than the vaguest of indications as to how they choose the content to serve. All we know is that Google’s ability to dive into long tail results means that the feed is capable of showing older content as well as immediate, breaking news style stories. Though it’s worth noting that all articles in this iteration of my feed were published in the last 24 hours.

Without much else to go on, I used a mix of observations, gut feelings and tools that we have access to here at Impression to try and work out how Google is sourcing the feed’s content.

Theory #1: AMP

AMP, or Accelerated Mobile Pages, is a familiar concept in SEO. We’ve already seen how important AMP functionality is if you want to rank well for informational search queries on mobile, be they news or general information articles. It’s not surprising, then, that 8 of the 10 stories on the first page of my feed were published on AMP.

While the presence of 2 non-AMP stories shows that Google isn’t completely excluding them, I think it’s clear that it’s better to have AMP-ready mobile pages if you want to give your content the best chance of appearing in the Google feed.

This observation is a start, but it’s fairly top level and doesn’t get at the specifics. What other ‘ranking signals’ might there be?

Theory #2: user search history

In Rand Fishkin’s recent Web Summit talk, he discussed the importance of user behaviour for SEO rankings. This basically means that sites you engage with are more likely to appear again for similar search queries that you make. For this theory, I only have anecdotal evidence, but I’m fairly sure this can be applied to the Google feed as well.

All of the Liverpool FC stories that I’ve seen on my feed, including the one you can see above, come from the Liverpool Echo. However, a News search for ‘liverpool fc’ features results from a wide range of sources, including the Daily Post North Wales, the Daily Star, The Sport Review, the Mirror and the Guardian, to name a few. But because I follow the Liverpool Echo’s LFC twitter account, @LivEchoLFC, I spend a huge amount of time on Liverpool Echo stories compared to any other sports site. This suggests to me that Google is using this data to realise that the Liverpool Echo is the best source to show me if it wants to keep driving clicks and getting me to come back to the feed. It could also be the case that other users interested in Liverpool FC also use the Liverpool Echo more than other sites, but I don’t have any data to back this hunch up.

I appreciate that there isn’t enough data to generalise confidently, but if Google is using behaviour signals in its feed’s algorithm then we need to be producing ‘sticky’ content: content that keeps users on the site and makes them want to come back for more. Often, the promotion of ‘sticky’ content is as important as the content itself, which means we also need to be savvy with social media and possibly even paid advertising to get the engagement that just might help us organically.

Theory #3: Google News results

The next thing I looked at was Google News. While I may be able to understand why I’m seeing stories from the Liverpool Echo, other stories seemed to come out of the blue, from sources I’ve never even heard of before. Why is Google deciding that these are worth showing me?

As many of these stories were news-style articles, I decided to search the topics into Google News (as you can see in the first screenshot, the associated topic appears at the top of each mobile card). I searched every single first page topic on my work computer (which has a different Google account logged in) and barely any of my feed’s stories appeared in the top results. The only topic with any similarity was ‘star wars: the last jedi.’ I repeated the searches on my phone (now using the same account as my feed) and found the same as desktop.

The bottom line is that ranking highly on news doesn’t seem to give your content a better chance of appearing for related topics in the Google app.

Theory #4: social shares

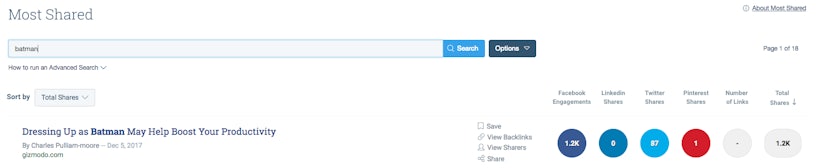

My next port of call was Buzzsumo. I entered the same topics into Buzzsumo’s ‘Most Shared’ tool and changed the setting to the last 24 hours (as all my feed’s content came within this time period). The results were more promising than my Google News search results, but still not conclusive. The most interesting was this one (and not just because the headline is wonderfully bizarre):

The top shared article globally, according to Buzzsumo, was the same as the Batman article that appeared in my feed. For the topic ‘theresa may,’ the article that appeared in my feed was the second most shared. However, for topics like ‘star wars: the last jedi’ (which we know lined up with Google News), ‘university’ and ‘cryptocurrency,’ the trending results didn’t have any relation. Switching the data to UK-only didn’t give me any other positive results, and actually dropped the ‘batman’ and ‘theresa may’ articles down the list.

Again, this is only a small data set, but it indicates that while social shares and engagement can line up with the Google feed results, it’s not a straightforward relationship. That said, as part of a ‘sticky’ content strategy, creating content that works in social feeds seems to be a positive signal to Google. It makes sense that Google would use social signals to influence this feed, which is designed to be very similar to the feeds you see on Facebook and Twitter.

Theory #5: Google trends

My final theory was that Google was pulling stories from its trending data. The app practically confirms some amount of this, with little ‘trending’ badges on some stories (though it doesn’t say in what sense they’re trending).

However, the top trending topics for the UK are, once again, completely different from the trending topics that appeared in my feed. My best guess here is that the articles that were shown to me were trending based on some number of engagement metrics, whether that’s social shares or clicks from other Google app users that the AI reckons are similar to me in some way.

Tapping into trending topics is a viable and proven PR strategy, but it doesn’t seem to have any direct bearing on the hyper-personalised content served in the Google app’s feed.

Optimising for Google feed

Where does all of this leave us? The different theories I’ve looked into indicate some broad guidelines, at least:

- Make sure your content is served on AMP.

- Create ‘sticky’ content that engages users.

- Promote content effectively to drive engagement and social metrics.

Some other ideas that seem logical, though they’ll take some more research include:

- Work out what topics your target audience is interested in and create content around those topics.

- Your efforts can be helped by formulating a PR strategy that includes ‘news-jacking’ and trending topics that your audience cares about.

- Continue to improve the authority and performance of your site.

One thing that I feel confident in saying is that your efforts will be helped by understanding the topics that your audience is interested in. Without this knowledge, you won’t stand a chance of reaching the right people.

My final point to mention is that all of the sites featured in my feed were predominantly content sites. I’m not sure, at this stage, whether it’s possible for company blogs to be featured. If you’ve seen examples of this, let me know in the comments! If you want to get your business to appear in Google feed, your best option might be trying to get guest posts, press releases or comments published on sites that are capable of appearing there.

Much of this is still guesswork. We also don’t know exactly how popular the Google feed is. Personally, I really like it. It feels less cluttered and more personalised than Facebook and Twitter. But will it catch on more widely, to the extent where brands really need to be there? Only time will tell.